Making Changes: Here’s How Transit Routes Get Adjusted

Hampton Roads Transit (HRT) operates nearly 300 buses along more than 60 fixed routes, serving thousands of riders daily across 438 square miles. Occasionally, service changes need to be made. Routes are extended, modified, or eliminated altogether. These changes can be extensive and require months, if not years, of planning. From planning to operations and facilities to technology, nearly every department in the agency is involved in the process.

“We make service changes to evaluate the efficiency of our network to improve service,” says Antoinette White, HRT’s interim director of planning and scheduling.

Improvements to service could be made to enhance on-time performance, create seamless transfer connections, increase frequency on high-demand routes, eliminate underperforming routes, modify routes to key destinations, or add service to fill gaps.

Service changes happen twice a year: in May, when the agency rolls out minor adjustments along with its seasonal VB Wave trolley service in Virginia Beach, and in the fall, typically October or November, when major service changes are made.

Service changes are scheduled according to HRT’s 10-year Transit Strategic Plan (TSP), first adopted by the Transportation District Commission of Hampton Roads in June 2020 and updated annually. White says some changes have been delayed due to a shortage of bus operators. HRT must get approval from the cities affected by the change before moving forward with any service changes that aren’t in the TSP.

Portsmouth changes

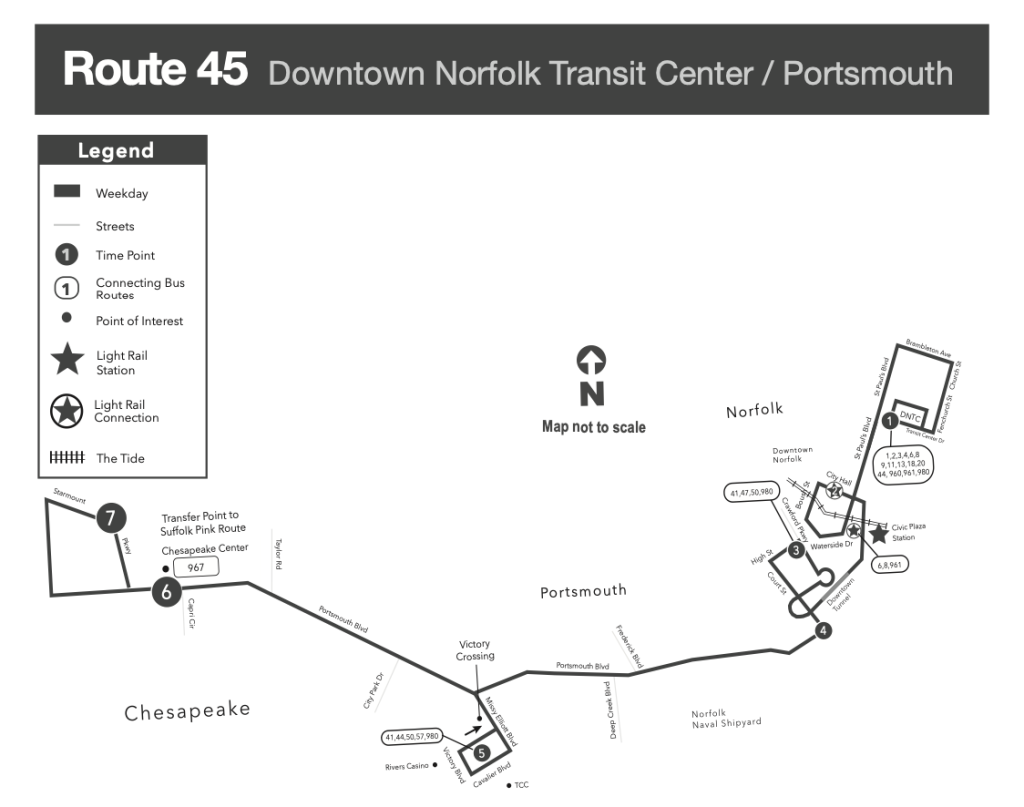

In October, HRT implemented two dozen route changes across its system. One of the biggest changes was to Route 45 in Portsmouth. The route was streamlined to cover most of Portsmouth Boulevard and extend into Chesapeake. Before the change in October, Portsmouth Boulevard was serviced by Routes 41, 45 and 44.

“There’s no longer a need for customers to transfer to another route,” White says. “What we’ve done is create a one-seat ride along Portsmouth Boulevard.”

Another service change in October was the elimination of Route 43 due to very low ridership.

When a service plan involves a major change, like eliminating a route, Jennifer Dove, HRT’s Title VI compliance officer, must thoroughly analyze the proposal’s impact.

The Federal Transit Administration (FTA) requires all transit agencies that receive federal funding to comply with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 requirements. It prohibits discrimination based on race, color, or national origin. It also prohibits discrimination against low-income and minority populations.

When analyzing any proposed service or fare change, Dove determines if the change will have a negative impact on low-income and minority riders more than non-minority and higher-income riders.

Dove must evaluate all proposed service changes and determine whether the proposed change will increase or decrease service miles or service hours by 25 percent or more than what is currently in place. If yes, it’s considered a “major” service change and will require further analysis under the Title VI guidelines. Of the two dozen routes changed in October, only two met the threshold for a “major” service change.

“If a route is eliminated, that’s more than 25 percent in service hours or service miles,” Dove says, “because it goes down from whatever it was to zero.”

Using HRT’s 2023 Origin and Destination Survey or U.S. Census data, Dove compares the percentage of low-income and minority populations living within ¾ of a mile of the route to the overall low-income and minority ridership for the system. If the difference is more than 5 percent, there could be a negative impact. In that case, HRT must develop a mitigation strategy. If a route is being eliminated, that mitigation strategy could include another route picking up part of the affected route.

“We might not be able to make it perfect, but we have to try to mitigate the impact,” Dove says.“ Ninety-nine percent of the time, we can come up with decent mitigation strategies.”

Feedback from customers

After Dove completes her analysis, she heads to transit centers and bus stops to get feedback from riders along the route. She wants to hear directly from passengers how they could be affected by the proposed change.

Finally, Dove presents her analysis and findings to the HRT Commission. According to the FTA, the Commission must only be made aware of the analysis. It does not require board approval.

Meanwhile, new schedules are created, bus stops are adjusted, signage is changed, and maps are updated. Bus operators and customer service representatives must receive training, and the Transit Riders Advisory Committee (TRAC) and Paratransit Advisory Committee must also be briefed on the upcoming changes.

As the service change date approaches, HRT’s Marketing and Strategic Communications team members begin their outreach to inform customers. That includes posting on social media, engaging the media, and hitting the ground to reach the public at transit centers and bus stops to hand out brochures and flyers, and converse one-on-one with passengers.

As an example of the type of outreach ahead of the October service changes, public outreach coordinator Yasmeen Oliver spent a lot of time meeting with riders in Portsmouth. While there was some apprehension, “customers were eager to understand the realignments and extended service hours,” Oliver says.

Outreach doesn’t end on game day. “To support customers,” she says, “additional outreach is scheduled over the next two months to collect feedback and provide assistance with navigating the new changes.”

HRT is in the middle of a system optimization study. The study should be completed next fall and is likely to bring the biggest round of changes to the system in decades. The agency will tackle these changes with the same care and creativity, always keeping the customer in mind, and doing its best to serve their mobility needs.